Every day, approximately 48.5 tons of space debris enter Earth’s atmosphere. While most of it falls into the ocean, never to be recovered, those that land on solid ground often ignite debates over legal ownership.

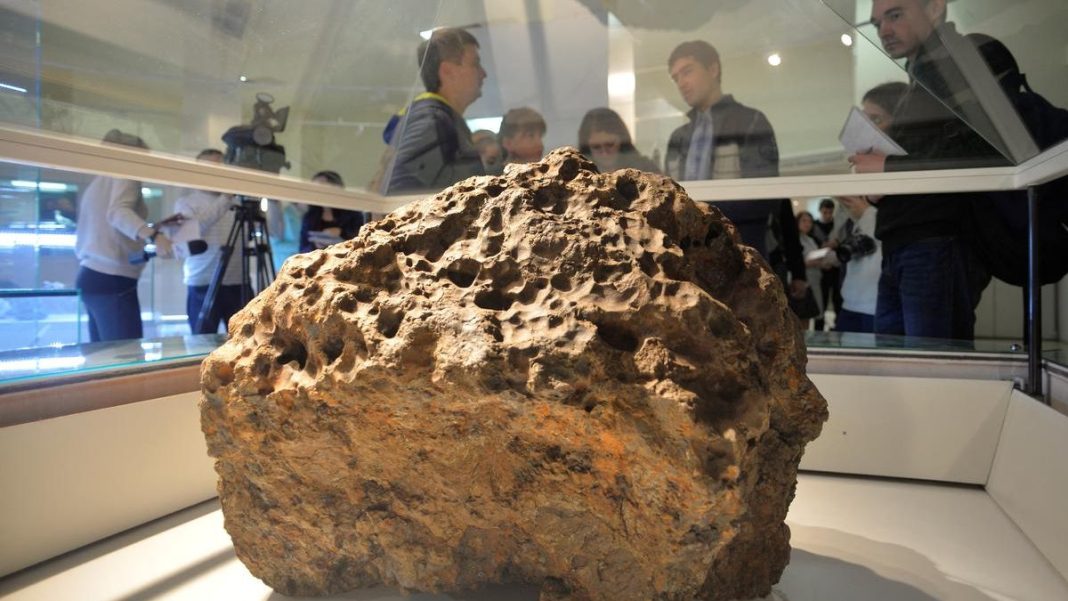

Meteorite hunting has evolved into a profitable industry, with extraterrestrial rock fragments being sold online and shipped globally. These space relics offer valuable scientific insights, yet many significant discoveries are being snapped up by private collectors, raising concerns within the scientific community.

In 2023, an apple-sized meteorite weighing 810 grams landed on conservation land in New Zealand’s central South Island near Takapō. It was discovered by Jack Weterings, a member of Fireballs Aotearoa, a citizen science group dedicated to tracking meteorites. This find has rekindled discussions around the legal framework governing such discoveries.

New Zealand has seen several notable meteorite falls in the past. One of the most famous incidents occurred on June 12, 2004, when a 1.3 kg meteorite crashed through the roof of the Archer family’s home in Auckland. The rock bounced off furniture before settling in their living room. Although the Archers received numerous purchase offers from around the world, they chose to sell it to the Auckland War Memorial Museum, ensuring public access to the rare find.

Meteorite Ownership Laws in New Zealand

Despite their celestial origin, meteorites are subject to the laws of the country where they are discovered. Different nations have varying regulations, with some permitting private ownership while others mandate state control without compensation.

New Zealand, along with countries such as Canada, France, the United States, and the United Kingdom, determines ownership based on the landing location. If a meteorite lands on private property, the landowner has legal ownership. However, when it falls on public land, as in the case of the Takapō meteorite, the “finders keepers” rule applies, making the discoverer the rightful owner. Fireballs Aotearoa, which claims no commercial interest, has pledged to donate all its finds to museums.

Not all meteorite hunters are as altruistic. The global demand for space rocks is growing, with commercial hunting gaining momentum, particularly in China, where meteorites can sell for millions. High-profile collectors such as Elon Musk, Steven Spielberg, Nicolas Cage, and Uri Geller have fueled the fascination with these cosmic antiques, further driving their value.

Regulating Meteorite Trade

Governments worldwide have taken steps to regulate meteorite hunting. In New Zealand, the export of certain cultural and scientific objects is strictly controlled under the Protected Objects Act 1975. This legislation aligns with international agreements, including the 1970 UNESCO Convention and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention, aimed at preventing illicit transfers of cultural property.

Meteorites are classified as protected objects under this law, meaning their export requires approval from the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. The chief executive of the ministry consults expert examiners before issuing an export license.

Unauthorized attempts to export meteorites carry significant penalties, including confiscation by the Crown, imprisonment for up to five years, and fines of up to NZ$100,000 for individuals or NZ$200,000 for corporations. If an export application is denied, the applicant can appeal to the Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage. If the appeal is unsuccessful, the meteorite is added to the nationally significant objects register.

Balancing Scientific Interests and Commercial Gain

Despite legislative efforts, tensions between private collectors and scientists persist. Some argue that meteorite collection should be discouraged unless strictly for scientific purposes. Whether a balance can be struck between preserving these extraterrestrial treasures for research and satisfying commercial interests remains to be seen.